The Luftwaffe's anti-aircraft artillery (Flak = anti-aircraft gun) was the heart of German air defense in the Third Reich. After mobilization in the autumn of 1939, around 258,000 soldiers served in the various air defense units or searchlight batteries of the Luftwaffe. The heavy air defense batteries included the variants of the 8.8 cm Flak, the 10.5 cm Flak and the 12.8 cm Flak, each of which was equipped with 4 guns in single or double mounts. In addition, there were the medium batteries with 3.7 cm Flak guns and the 2 cm Flak units. Their task was to protect objects in connection with the defense against incoming fighter aircraft on the then Reich territory. There were also units of the army anti-aircraft divisions to protect the ground troops, which were used not only for air defense but also to attack ground targets. It was primarily equipped with the mobile heavy 8.8 cm anti-aircraft gun and the light 2 cm anti-aircraft gun. The 8.8 cm cannon in particular proved to be particularly effective in ground combat against ground targets. Its high penetrating power against hard targets gave the enemy a feared reputation.To protect the coastal strip and its warships, the Kriegsmarine had its own land-based anti-aircraft artillery and ship-based air defense. Around 100,000 naval artillery soldiers who were trained in the appropriate weapons were deployed. The initial main problem with the anti-aircraft guns in wartime operations was the inadequate electronic detection of enemy aircraft and the resulting high ammunition consumption. Despite the additional equipment with measuring devices and technical developments, the radio measuring devices were repeatedly disrupted by various influences.From 1944 onwards, forces from the Reich Air Defense were often transferred to the ground fronts as soon as enemy forces approached the German Reich's borders. But already from the middle of the war, young anti-aircraft helpers were deployed in the batteries to compensate for the heavy loss of personnel from seconded anti-aircraft artillerymen. These were graduating schoolchildren, Hitler Youth, members of the BDM, the RAD or prisoners of war who were deployed as so-called volunteers. Another problem was the increasing shortage of ammunition. After the war, the United States Army Air Forces (USAAF) reported that German anti-aircraft guns had shot down 5,400 US aircraft. On the Eastern Front, around 17,000 enemy aircraft were shot down by anti-aircraft artillery. Sources: Old Flakleitstand-Nordenham / MB.

The anti-aircraft battery

A 10.5 cm anti-aircraft gun from the Drangst battery fires a salvo at incoming bombers.

Heavy anti-aircraft fire on a group of American Boeing B 17 bombers.

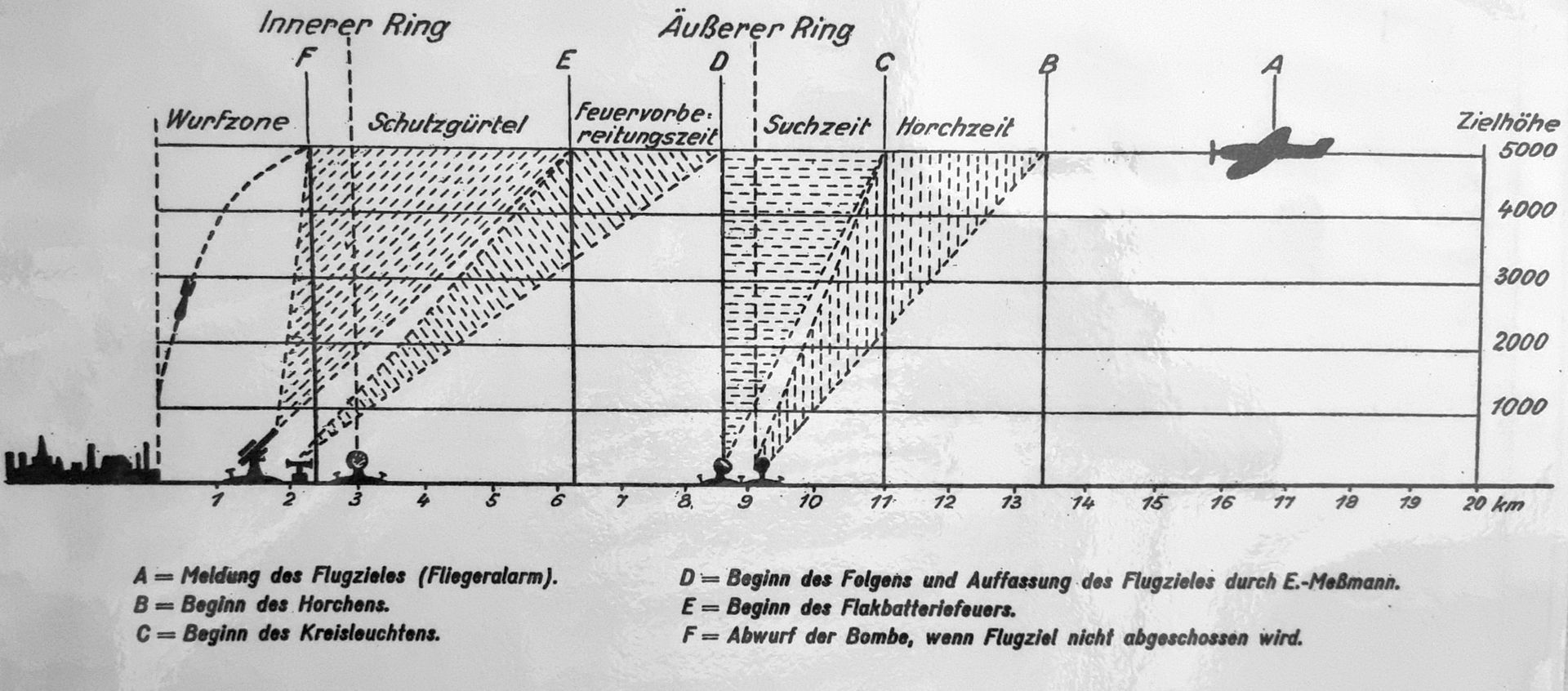

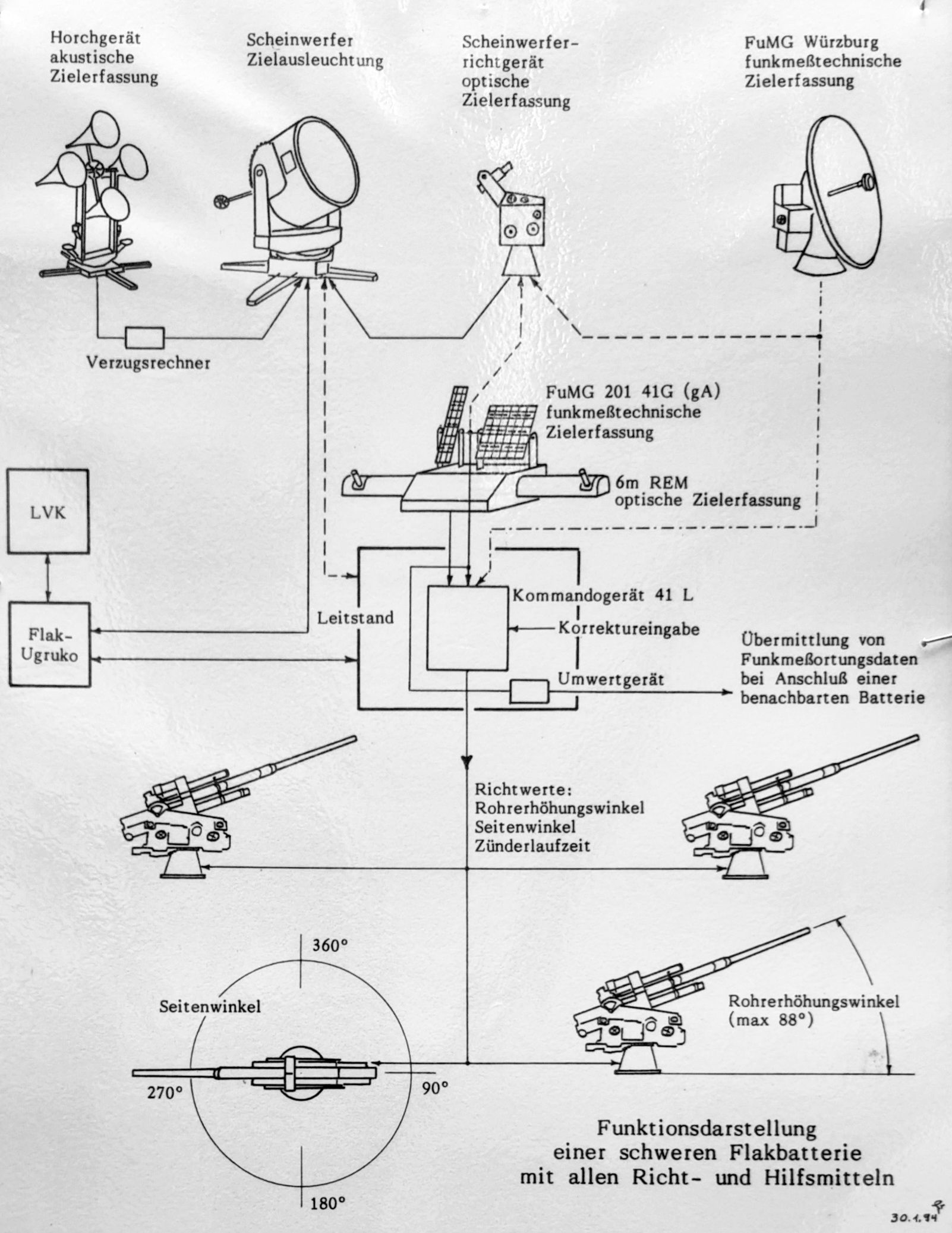

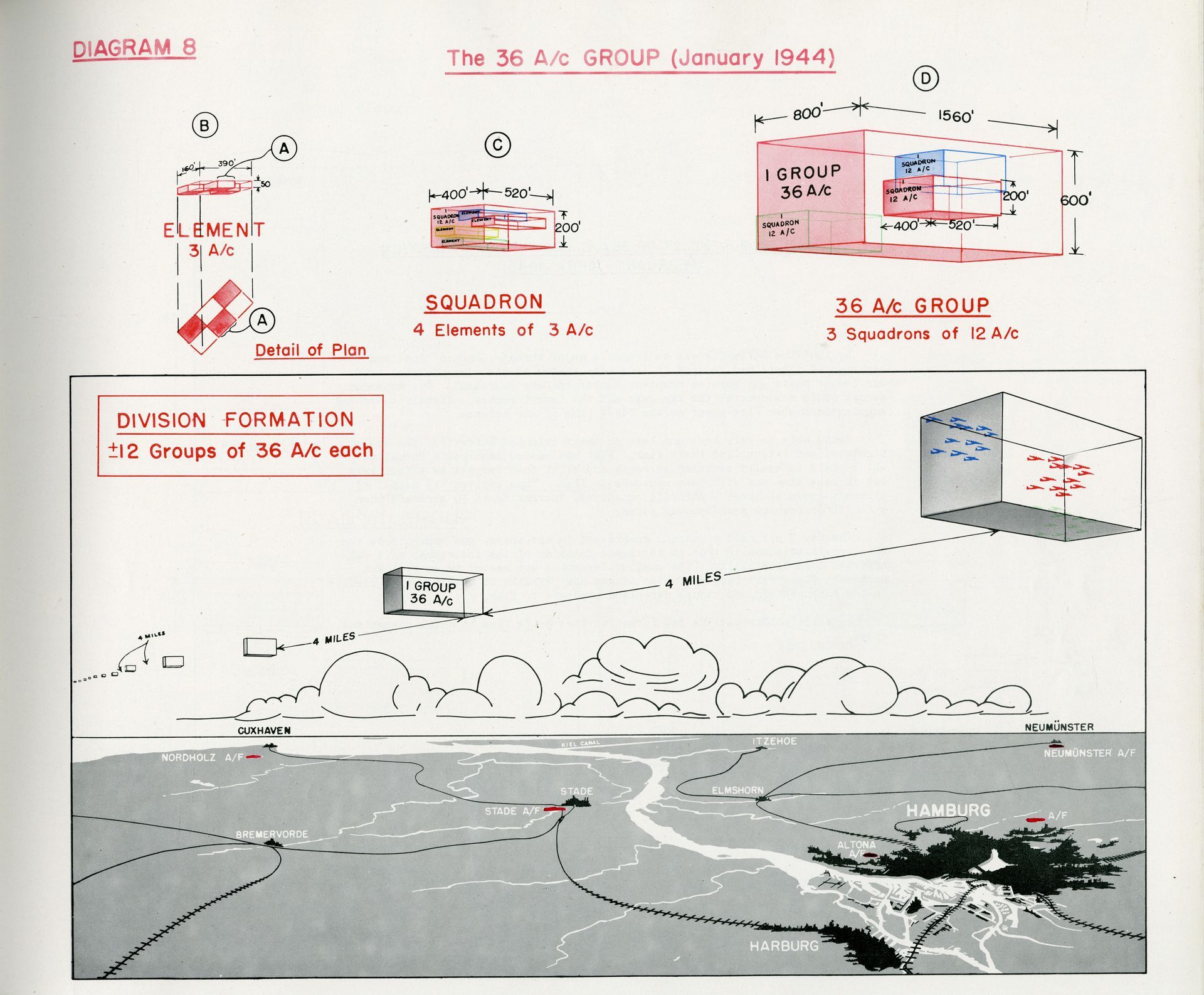

The anti-aircraft batteries usually consisted of four guns each, which were electrically controlled and detonated. The aim was to fire the projectiles synchronously and place them in the air so that the four grenades exploded simultaneously within a radius of around 55 meters from the target. To attack an aircraft at an altitude of 4000 m, the fired grenades needed around 6 seconds. During this time the aircraft covered around 480 m. The gunners therefore had to hold up. The relevant data for this was provided by the command device and the visual optics. Thanks to the technology and the interaction of the anti-aircraft crew, around 21 seconds passed from target acquisition to detonation of the grenades. 10 seconds for the command device to acquire the target, 5 seconds for setting the ignition and loading the guns, and 6 seconds for the fired grenades to travel back to the target. A well-coordinated team achieved a rate of fire of 5 seconds.

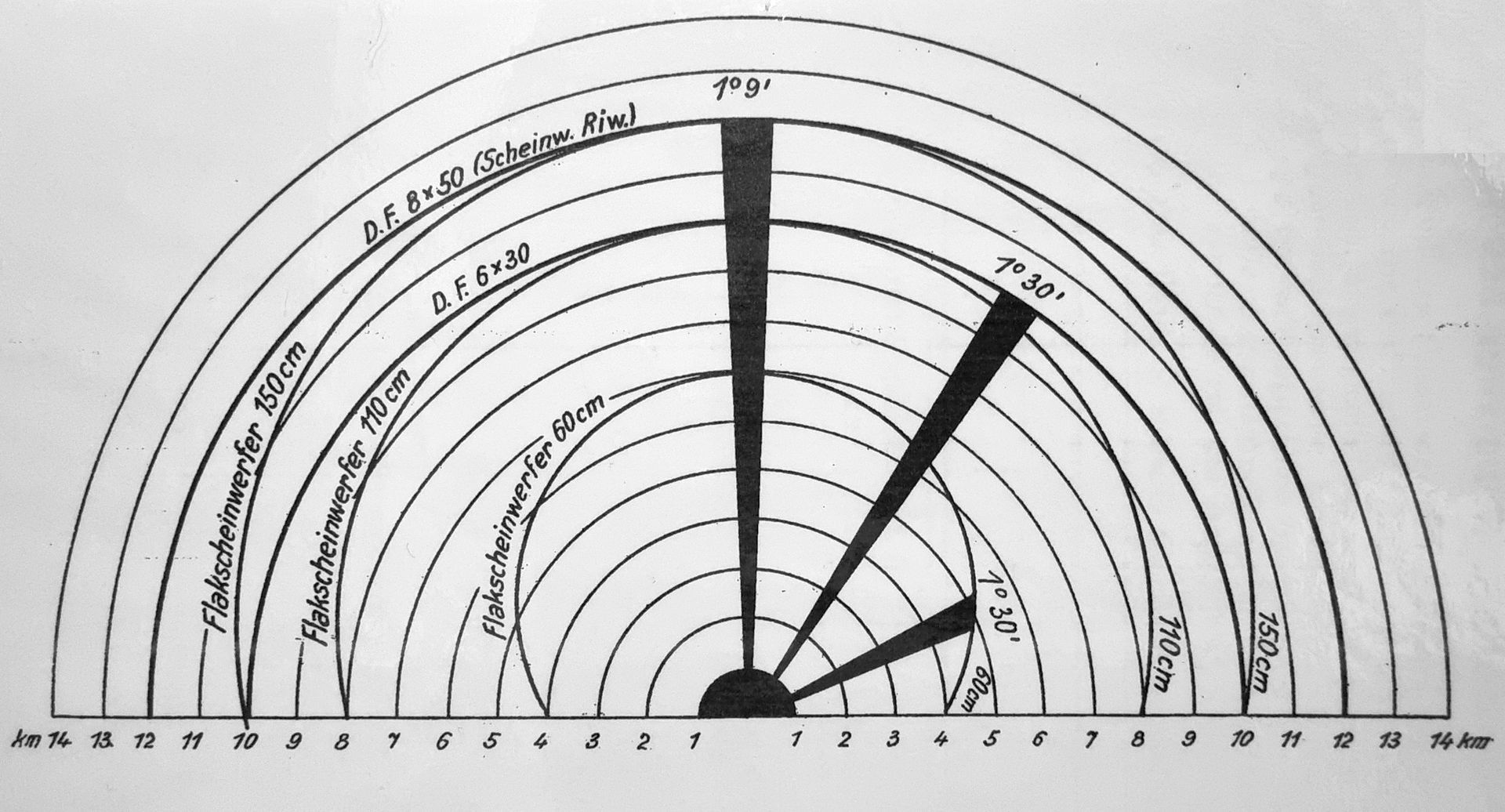

Theoretical use of a 150 cm anti-aircraft searchlight in conjunction with the heavy anti-aircraft guns.

By means of advanced directional listeners and corresponding anti-aircraft searchlights, air targets attacking at an altitude of 5,000 meters could be detected as early as 13,000 meters in front of the object to be protected.

Sources: Old Anti-Aircraft Control Station-Nordenham / MB.

The effect of the anti-aircraft gun

The success of the anti-aircraft guns used against air targets depended on the operator and the command device - the fire control system. The computer system of the command device processed the recorded data from the previous flight route and altitude of the aircraft. It then delivered corresponding data in the form of altitude and lateral direction indicators. This calculated the flight time of the grenades and the associated fuse setting. For these settings there was a fuse setting machine in which the grenades with the fuse were placed upside down and the clockwork fuse was automatically set. The fuse setting determined the time - and thus the flight altitude - at which the fired grenade exploded. When detonated, the grenade - for example an 8.8 cm grenade - is broken up into around 1500 fragments, which spread in all directions at high speed. An aircraft that was less than 10 m away from the detonation point was so badly damaged that it usually crashed. Even at a distance of 180 m, an aircraft could still be seriously damaged. The extremely high air pressure created when the grenade detonated could also have serious consequences for the aircraft and, not least, for the crew. As the war progressed, the grenades were equipped with a combined time-impact fuse. This prevented the projectile from flying through the aircraft without exploding in the event of a direct hit.

Der Respekt vor der deutschen Flak wurde vom Gegner hoch eingeschätzt. So gab die 9.US. Luftflotte an, dass 49,6 % der Abschüsse und 92,6 % der Flugzeugbeschädigungen durch die deutsche Flak erzielt wurde. Statistisch war mit einem Abschuss eines 4-motorigen Bombers zu rechnen bei einen Einsatz von :

- 16000 rounds of the 8.8 cm Flak Mod. 36/37 8500 rounds of the 8.8 cm Flak Mod. 41 6000 rounds of the 10.5 cm Flak Mod. 39 3000 rounds of the 12.8 cm Flak Mod. 40

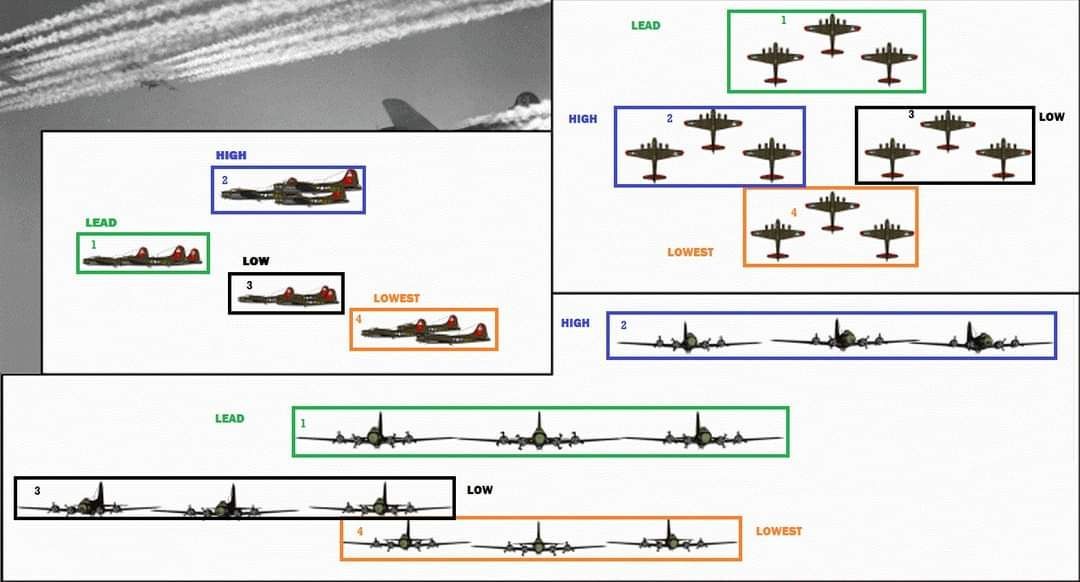

These figures show how ineffective the anti-aircraft guns actually were. But apart from the fighter planes, there was no other means of combating the increasingly powerful bomber formations. Direct shots down by the anti-aircraft batteries were not always the norm, but the effect of the shrapnel on the Allied fighter planes was high. The planes were, however, very robustly built, so that they remained airworthy even if two engines failed. Even if wing segments or large airframe structures were completely blown away, the planes did not necessarily crash immediately. Despite this, many bombers were lost on the return flight to their home base or crash-landed on landing. Many planes were severely damaged and went down over the North Sea on the return flight, with the crews usually dying completely and never being found. The effect of the shrapnel on the crews in the planes themselves was also serious. Despite armour and splinter protection in places, many aircraft crews were killed or seriously injured by the anti-aircraft fire. Although the success of the air defence was not so effective due to only a relatively small number of direct shots down, the heavy fire from the ground had a different effect. For their own protection, the bomber squadrons flying in over the mainland had to fly much higher. This made it more difficult for the aircraft to aim precisely at the objects they were looking for on the ground.

Sources: Old Anti-Aircraft Control Station-Nordenham / MB.